views

Johannesburg — The Minister of Health for the Democratic Republic of Congo, Samuel Roger Kamba, confirmed last week an outbreak of the highly infectious Zaire strain of Ebola virus disease in the country’s Central Kasai Province. He said 16 deaths and 28 suspected cases had been confirmed, including four suspected infections among health care workers.

World Health Organization regional director for Africa Mohamed Janabi said the first case, known as the index case, was a “34-year-old pregnant woman who was admitted on August 20 and passed away on August 25 with typical features for hemorrhagic fever; bloody diarrhea, bleeding from the nose, vomiting, and bleeding from the rectum.”

The Ebola virus is transmitted to humans through close contact with infected wildlife, often bats, and can then spread through bodily fluids through close human-to-human contact. The WHO said that, as of Sept. 4, the case fatality rate in the Congo outbreak was 57%, with 80% of the cases in people aged 15 or older.

This is the sixth Ebola outbreak within seven years in Congo, making it the highest concentration of outbreaks since the virus was first discovered in 1976.

A team of first responders arrived Sunday in the Bulape health zone, where the outbreak has struck, with medical supplies.

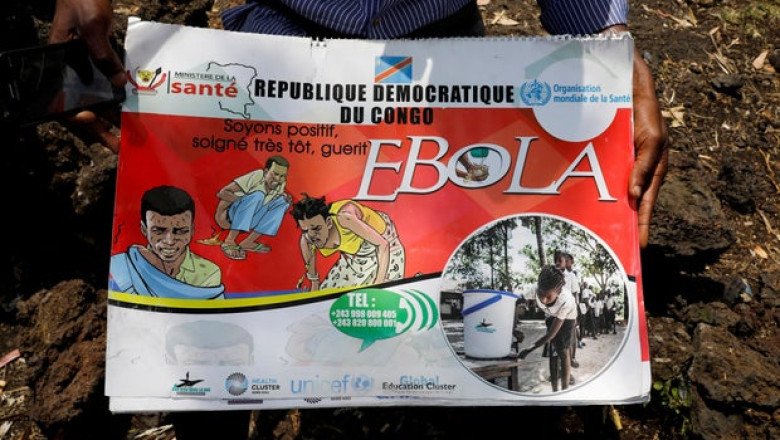

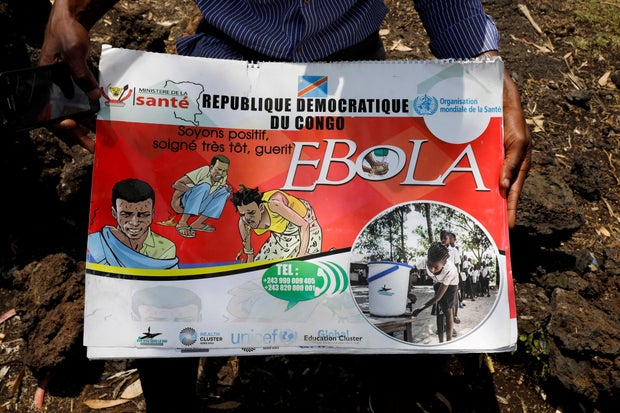

Congolese volunteer Ferdinand Tangenyi displays a flip book he uses to inform people about the Ebola virus, in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, in an Aug. 3, 2019 file photo. Baz Ratner/REUTERS

In the country’s capital Kinshasa, health workers and first responders from the Ministry of Health, the WHO and the Africa Centers for Disease Control and Prevention were given vaccinations ahead of deployments to the affected region.

Congo currently has a stockpile of 2,000 vaccine doses and has ordered more to arrive in the coming days, according to the WHO.

Patrick Otim, the WHO’s emergency response coordinator for the area, told reporters during a Sept. 4 briefing that the United Nations agency was already working to trace close contacts with known cases, increase field lab testing capacity and community response to ensure early reporting.

He acknowledged that the DRC had requested additional vaccines and stressed that, as “early supportive care is key to lifesaving,” the WHO was working to deliver more medical supplies, including protective clothing and other items “necessary to manage the outbreak.”

The last two outbreaks, in 2022, were contained quickly, said Otim, but he noted that they were addressed before the Trump administration severely cut funding for international health programs, including the WHO.

A photo taken on March 21, 2021, shows a medical worker vaccinating a local resident against the Ebola virus in North Kivu province, Democratic Republic of Congo. Alain Uaykani/Xinhua/Getty

Those cuts have fueled concern in Africa and elsewhere about the ability of individual nations and global agencies to respond to and quickly contain outbreaks of diseases including Ebola — and to keep such deadly viruses from reaching U.S. shores.

“The recent cuts will definitely have an impact,” Otim said at the briefing. “As a global community, we need to work together to stop this virus, as diseases do not respect borders.”

“What we know (from past outbreaks) is you need to get supplies and resources as soon as possible to stop transmission,” Otim added.

President Trump announced in January that the U.S. — long a key stakeholder and largest donor to the agency — would be pulling out of the WHO, with the White House citing “the organization’s mishandling of the COVID-19 pandemic that arose out of Wuhan, China, and other global health crises, its failure to adopt urgently needed reforms, and its inability to demonstrate independence from the inappropriate political influence of WHO member states.”

The Trump administration, at the time, also accused the WHO of demanding “unfairly onerous payments from the United States, far out of proportion with other countries’ assessed payments.”

The WHO warned almost immediately that, given the uncertainty over future U.S. funding, it was cutting back spending in ways that could impact its operations.

Congo’s health care system was already overburdened as it battles to contain an mpox outbreak, with roughly 130,000 suspected cases since last year and about 2,000 deaths now recorded, the WHO said at the briefing last week.

Complicating the response is the fact that the nearest medical isolation unit to the outbreak only has 15 beds, and road access from Kinshasa can take up to three days, further delaying the arrival of medical teams and supplies.

The WHO has already delivered about 13 tons of emergency medical supplies to Congo to help contain and treat the outbreak.

Other African nations have put border entry points and health facilities on high alert to detect any possible Ebola cases.

More from CBS News

Sarah Carter is an award-winning CBS News producer based in Johannesburg, South Africa. She has been with CBS News since 1997, following freelance work for organizations including The New York Times, National Geographic, PBS Frontline and NPR.

https://wol.com/as-ebola-outbreak-kills-16-people-in-congo-who-official-says-trumps-aid-cuts-will-definitely-have-an-impact/

Comments

0 comment